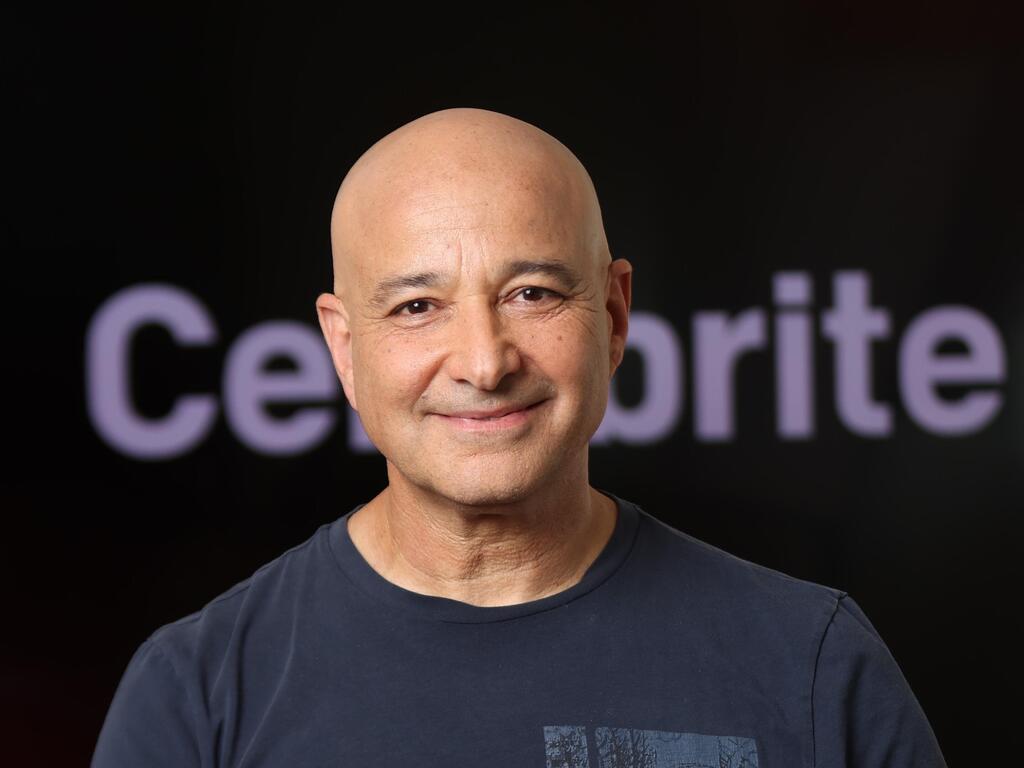

From bootstrapped startup to a $5B powerhouse: Cellebrite's outgoing CEO reflects on 19 years of highs and controversies

Yossi Carmil on Cellebrite’s rise, its human rights challenges, and why he’s stepping down at the peak of success.

The mission of most CEOs on Wall Street, especially those leading high-tech companies, is to convince investors that their company is more exciting than the competition. The concept of an "equity story"—essentially, how to excite potential investors and persuade them to buy your company's stock over the hundreds of others on the Nasdaq—requires managers to be creative. For Yossi Carmil, the outgoing CEO of the Israeli company Cellebrite, the mission over the past four years, during which the company was publicly traded, was the exact opposite.

"If I had to describe Cellebrite with a word that starts with the letter 'S,' it wouldn’t be 'sexy' but 'safety,'" says Carmil in an exclusive retirement interview with Calcalist. In recent weeks, Carmil celebrated the end of his tenure with Cellebrite employees in Israel, the U.S., and Germany at three separate parties before embarking on a family trip to South America. But as much as Carmil tries to portray Cellebrite as a dull company from Petah Tikva that simply helps law enforcement agencies bring digital evidence to court, his 19-year tenure at the company was anything but uneventful.

While Cellebrite positions itself as a company that assists law enforcement, primarily selling its technology to police forces for extracting information from seized devices, controversies have erupted time and again. Just last month, an Amnesty International report accused Cellebrite’s software of being used to track journalists and protesters in Serbia.

According to the report, Amnesty received testimonies from journalists and protesters claiming that their phones had been hacked and monitored in recent months using Cellebrite technology. In two cases, the devices were allegedly hacked using Cellebrite, with their contents—such as contacts—copied to a government server before being "infected" with surveillance software.

Some journalists and activists reported noticing suspicious activity on their devices shortly after being summoned for questioning by Serbian police and security authorities. Such incidents have plagued Cellebrite over the years, repeatedly forcing the company to explain how its software ended up in the hands of unauthorized users and, in some cases, leading to its withdrawal from operations in countries such as Russia, Hong Kong, and China. These controversies have also caused some investors—and even potential employees—to associate Cellebrite with cyber-surveillance companies like NSO.

"That perception is outdated," Carmil asserts. "When we were a private company, we didn't talk about it much, but since going public, we've worked hard to make it clear—we are not, and have never been, a spy company. The IPO really helped us clarify our role, and the proof is that we've passed the most stringent investment committees of major institutional investors like Fidelity and Wellington, which now hold significant stakes in Cellebrite. The explanation is simple: our platform is only relevant after evidence has already been seized. We come into play after evidence is collected at a crime scene or obtained under a judge’s order. At that point, we use our tools strictly within the confines of the law."

But you don’t always know who will ultimately use your software or how it will be applied. In the Serbian case, for example, Amnesty International reported that the Cellebrite software was originally purchased by the Norwegian government to fight organized crime and help modernize Serbian law enforcement.

"It has become a national sport to paint Cellebrite as operating in a gray area, but that’s simply not the case. I led this company for 19 years and was always asked about this issue. What I can say is that we operate in countries that follow the law and work exclusively with legitimate enforcement agencies. We are far more boring than people think—we are neither secretive nor classified. In fact, most of our government tenders are publicly available online."

Still, you needed approval from Israel’s Ministry of Defense to export your solutions.

"For many years, we didn’t require such approval. But that has nothing to do with legality—it’s about the sensitivity of the technology. Cellebrite is regulated because its technology qualifies as dual-use, just like firearms or electronic surveillance fences. The existence of regulation is purely a matter of Israel’s export control policies and has nothing to do with how, for example, the German police use our platform. Law enforcement agencies and Nasdaq investors understand that Cellebrite plays a key role in public safety."

The best Israeli SPAC in terms of return

It’s no coincidence that Carmil frequently brings up Cellebrite’s IPO. Last weekend, Cellebrite crossed the symbolic $5 billion market cap for the first time in its history, solidifying its status as the most successful SPAC offering by an Israeli company in terms of return—and one of the top five globally. Over the past year, Cellebrite’s stock has soared 150%, with its current valuation more than doubling the value it received in its 2021 SPAC merger.

Cellebrite’s path to going public wasn’t without challenges. Ahead of its IPO, a group of human rights organizations published an open letter calling for the Israeli company to be blocked from listing on Wall Street.

“In hindsight, I wouldn’t recommend SPAC to anyone,” Carmil admits. “We chose the SPAC route because we had a perception problem—we were mistakenly associated with the offensive cyber field. We thought a strong SPAC partner would help us go public faster and reshape our image. But in practice, we quickly realized that we had simply swapped one label for another. We were branded as a SPAC company, and that label stuck with us.

“We could have pursued a traditional IPO,” he continues, “but SPAC seemed like the faster route and promised a larger fundraising. In reality, it was slower, and by the time we reached Wall Street, we had lost momentum. Instead of raising $600 million as planned, we ended up with only $70 million, because investors exercised their right to redeem funds. Our valuation in the deal dropped from the expected $2.4 billion to $1.8 billion. Today, I’d advise CEOs to take their time, educate investors about their company, do the groundwork in the market, and only then go public.”

Yet as Carmil reflects on his tenure, he sees the IPO as his most significant achievement—one that now allows him to retire in peace. “Another lesson in hindsight is that Cellebrite should have gone public through a traditional IPO much earlier. But because we were bootstrapped (without venture capital funding), we got complacent. Our Japanese shareholders never invested additional capital and also delayed our progress. When you have a dominant shareholder, you can become stagnant, and that can be dangerous for a company. Everything changed in 2019 when the Israeli IGP fund, led by Haim Shani and Moshe Lichtman, invested $100 million, diluted the Japanese board members, and woke us up. Had we gone public earlier, we would have scaled faster. The IPO not only forced us to better articulate what we do but also required us to explain our growth model. That’s how, even after parting ways with weaker results in 2022, we set a clear path—from projected revenues of around $400 million in 2024 to $1 billion by 2028.”

Why retire now, when the stock is at its peak and you’ve given strong forecasts for the years ahead?

“They always say that being a CEO is a lonely job, but at the end of the day, CEOs are human, too. After 20 years with the company, I’ve reached a point where I have to acknowledge that I’m exhausted. There were many factors in my decision: I’m approaching my 60s, the company has doubled in value since the 2022 crisis, we now have 1,150 employees, and we are in a strong market position. It’s a mix of success, exhaustion, and the desire to step away from the race. Of course, there’s a chance I’ll regret it.”

That’s the official explanation, but Carmil also offers a broader perspective on the challenges facing Israeli high-tech:

“There’s strong management talent in Israel today, but you can only run a company from here up to a certain size. When a company nears $1 billion in annual revenue and aims to become a truly global enterprise, it becomes increasingly difficult—if not impossible—to manage it from Israel. Either you transfer leadership to foreign management, or you physically relocate to the U.S. I spent years living between two homes—one in Washington, away from my family, and the other in Herzliya. I had seriously considered moving to the U.S. full-time, but the war strengthened my desire, and my family’s, to stay in Israel. Since I want to remain here, I understand that the next CEO needs to be based in the U.S. and lead the company from there.”

A long affair with the Japanese

The story of Cellebrite is not the typical Israeli startup story, and the "Japanese" that Carmil now speaks of with little affection are an integral part of it. Although he is not one of the company's founders, Carmil’s journey is inseparable from Cellebrite’s history. He joined the company in 2004, when it was a five-year-old startup developing hardware and software for mobile operators and retail stores, enabling the transfer of contacts and photos between devices—such as from Sony Ericsson to Nokia. Before that, Carmil was a lieutenant colonel in the paratroopers, serving under Benny Gantz as his battalion commander.

After his IDF service, he worked at the Ministry of Defense and was posted to Europe, where he decided to stay and study business administration, riding the wave of optimism surrounding the early 1990s European Common Market. At 37, following the death of his sister from cancer, he returned to Israel and briefly served as VP of commercial operations at Siemens Israel. Just over a year after joining Cellebrite, in 2005, he was appointed CEO alongside Ron Serber (who retired in 2020). At the time, Cellebrite had only 18 employees and an annual revenue of $5 million.

In 2007, it seemed that Cellebrite was making an exit—at least by the standards of the time—when the company’s founders, Avi Yablonka, Yaron Baratz, and Yuval Aflalo, sold their shares to the Japanese corporation Sun for $17.5 million. Carmil also sold some of the shares he had received in Cellebrite for several hundred thousand dollars but chose to remain with the company. This marked the beginning of what he now calls a “love affair” with the Japanese—one he believes lasted too long.

"After the sale to the Japanese, we recognized that digital forensics was an emerging field, but we were no longer the first in it. We also realized that mobile phones would become increasingly central to daily life and play a significant role in future investigations," said Carmil.

What did law enforcement have to do with mobile phones at the time?

"Back then, investigators primarily retrieved photos from phones, but judges started asking how they could verify their authenticity. We provided the certification that the photos were genuine, and over time, we became an essential part of the launch process for new mobile devices—every phone that entered the market was sent directly to our lab in Petah Tikva. But the real breakthrough came in 2009, when we became the first company to successfully extract information from a phone. From that point on, we established a technological advantage over our competitors that remains unmatched to this day," Carmil explained.

Cellebrite’s reputation became so prominent that in a 2011 episode of the popular TV series CSI, it was stated "officially" that nothing could be permanently deleted from a phone anymore—thanks to Cellebrite.

Beyond its pop culture references, Cellebrite has been involved in numerous real-life investigations, from the 2009 Bar Noar shooting in Tel Aviv—where police recovered a deleted WhatsApp message that led to the acquittal of the accused—to the 2015 Bataclan terror attack in Paris and, more recently, the attempted assassination of U.S. President Donald Trump at a campaign rally last summer. In that case, the FBI successfully extracted data from the suspect’s phone using Cellebrite’s software in just 40 minutes.

Following the October 7 massacre, Cellebrite provided its platform pro bono to help grieving families recover photos and messages from burned and destroyed smartphones. In Israel’s ongoing security operations, when reports state that “terrorists are still at large,” it often means that Cellebrite’s software is being used to analyze seized mobile phones to identify accomplices and track their movements.

Why hasn’t Cellebrite reached a billion-dollar revenue sooner?

Despite its dominance in digital forensics, Cellebrite only recently projected reaching $1 billion in annual revenue by 2028. If the company is the industry’s "gold standard," why didn’t it achieve this milestone earlier?

"We are not a young company, but our initial market was much smaller—only a few hundred million dollars. Had we not expanded into real analytics and portfolio management tools, we would have remained a niche player. In 2019, I led Cellebrite’s transformation into a comprehensive platform for managing all digital evidence, creating a broader category. The $1.3 billion acquisition of our competitor Magnet by Thoma Bravo is proof that this market is real and growing," Carmil said.

He highlighted the unique advantage Cellebrite has over companies like NSO Group, which focus on cyber surveillance: "There’s a certain appeal to tracking and monitoring like NSO does, but when you have physical access to a device, you can uncover much more than just deleted messages. The phone holds a wealth of data—location history, hidden files, app logs—and even when connected to a car, it creates an entirely new layer of evidence. The car itself becomes a digital crime scene, retaining records of every phone connected to it. Even a WhatsApp message deleted 20 years ago can be retrieved. Today, we aggregate data from mobile phones, computers, license plate readers, routers, security cameras, voice recordings, and even cryptocurrency transactions to create the 'golden evidence' for conviction."

The cost of bootstrapping

Carmil also offers a cautionary lesson for startups considering the bootstrapped route: "It’s great to be bootstrapped, but it comes with costs. At some point, you have to be hungrier and stop living hand to mouth. We were always profitable, but we were operating in a very small market. The Japanese gave us full operational freedom, but that also kept us in a niche for too long. We’re only now breaking into the broader market. IGP’s investment in 2019 wasn’t because we needed the money, but because it allowed us to make a strategic leap. Haim Shani, a former CEO of NICE, gave us the backing to take bold steps as chairman of Cellebrite. In hindsight, we could have made these moves two or three years earlier."

Despite his criticism, the Japanese still hold a substantial stake in Cellebrite and remain on its board of directors.

What’s next for you?

"There aren’t many CEOs in Israel who have sold a company to the Japanese, bootstrapped their way to a Wall Street IPO, and led a successful SPAC. I expect to contribute mainly as a board member or investor in young startups. Despite the challenges of the past few years, Israel’s high-tech ecosystem remains strong. Foreign investors are eager to return. While everyone is focused on AI, I believe in and am involved in defense tech—there will be significant investment in this field. I’ve already seen promising ventures, and I’m sure more will emerge. It’s both a global challenge and a global opportunity."

What's the biggest challenge for Israeli high-tech?

"The increasing number of professionals moving abroad. It’s a serious and dangerous trend. There’s a constant rise in employees requesting relocation due to security concerns and political instability. I lived in Europe for ten years, and without Israel, no one has real security. Anyone who thinks otherwise is living in an illusion. That’s why we must fight the phenomenon of talent leaving the country."